PSYCHONAUTS

Psychonauts is a 3D-platforming video-game released in 2005, created by Double Fine Studios and published by Majesco. It would later-MUCH later-recieve two sequels: a VR-exclusive adventure game called Psychonauts in the Rhombus of Ruin, and a proper 3D-platformer called Psychonauts 2.

It is also my favourite video game of all time.

Psychonauts takes place in a 60s-ish science-fictional universe, in which some people

have psychic powers.

Aside from the more typical psychic abilities, such as telepathy, telekinesis, lighting things on fire with your mind, communing with animals, and so on, psychics are also able to enter metaphysical representations of other people's minds.

(This is all far less pretentious than it sounds.)

'Mental worlds' appear as a variety of cartoonishly surreal landscapes, representing the memories, personality traits and mental illnesses of their owners.

A stoic superspy's brain takes the form of a giant cube that folds in and out of itself, displaying wildly different aspects of his memories and personality.

A paranoid schizophrenic man's appears as a twisted 1950s suburban neighborhood, chock-full of hidden cameras and government agents.

So on and so forth.

Psychonauts follows one Razputin Aquato (usually just called Raz), a ten-year-old boy who runs away from his home in the circus to a summer-camp for training young psychics called Whispering Rock. Whispering Rock is ran by the titular Psychonauts, an international espionage-slash-psychotherapy organization made up of highly-trained, highly-eccentric psychic super-spies.

Between his lessons, taken against his father's wishes, Raz begins to uncover a conspiracy, involving dentists, meat, an abandoned asylum, and the Psychonauts themselves..

Despite it's out-there premise and absurd humour, Psychonauts covers some serious topics-mental illness, autism, growing up and especially growing up with autism-very well.

Essentially, it's a very classic coming-of-age story wrapped up in a package somewhere between Invader Zim and James Bond, with some Kurt Vonnegut to taste.

That might sound totally dissonant, but it works somehow.

Those topics are rather personal to me, and I felt that this game captures the strange, disconnected feeling of growing up 'different' from your peers in a way that's hard to articulate very, very well.

It's also got a giant mutated sentient lungfish named Linda,

so it's basically perfect in every way.

GAMEPLAY

Psychonauts is a 3D platformer, but it shares a number of design principles with point-and-click adventure games.

What I mean by that is that puzzles are largely logic-based and rely more on an outside, common-sense understanding of things, rather than an understanding of game mechanics. It's not so much a "put psychic power A into slot B" situation as it is a "hey, there's a chair blocking this door, but I can't reach it; maybe if I use telekinesis I could move it out of the way?" sort of deal.

Does that make any sense? Whatever.

Point is, the puzzles are well-thought-out and have to be thought about a bit. They vary in mechanics wildly, and no two puzzles feel the same-and no two mental worlds do, either.

Waterloo World, for example, consists entirely of puzzling out a board game (and puzzling out how to get your pieces to listen to you). Gloria's Theater involves switching around mood-swing lighting and stage props to put together horribly-acted plays, revealing Gloria's memories as you go along. The Meat Circus has almost no puzzles at all, in keeping with it's oppressive, frantic atmosphere.

Raz ponders some items, used in the Milkman Conspiracy as disguises.

That's not to say the platforming isn't worthy of praise; the same kind of thinking went into those mechanics, too, and the end result is really fun. Raz is an acrobat, technically, so he has a number of neat platforming abilities along with his psychic powers.

Things like swinging around on bars and walking along tightropes lend some extra texture to platforming sequences, along with the unique look and feel of every part of the game. Climbing up through an abandoned asylum, rail-grinding along a structure held up by fans and lava-lamps, racing other campers on a levitation ball..

Of course I can't really describe it through text, but the 'feel' of the platforming and controls is excellent.

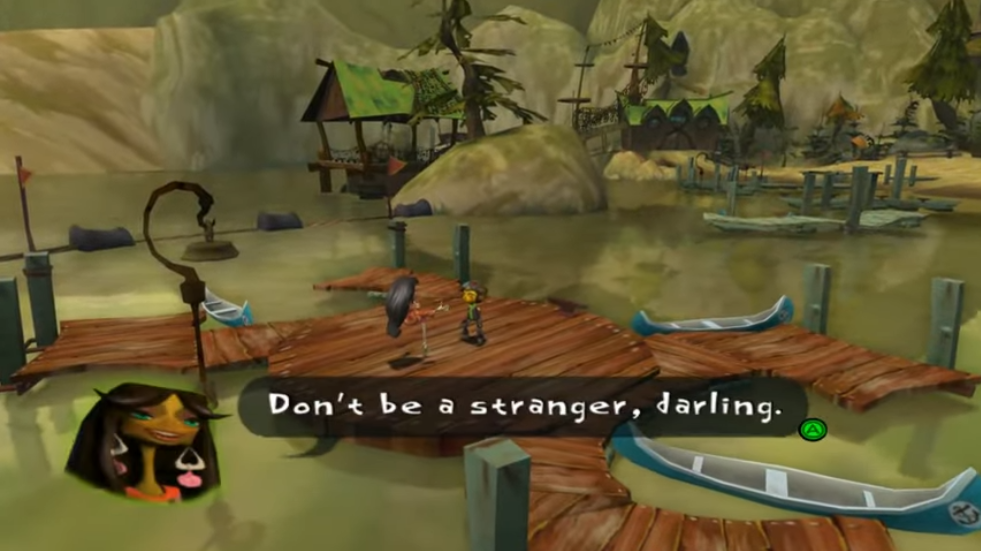

One of the many draws of Psychonauts is the level of detail present in NPC dialogue:

Every item and ability you get can be used on or shown to every character, and they all have unique, fully-voiced dialogue for most of them. This includes situations that are normally impossible to encounter without cheating; characters encountered earlier in the game have their own responses to psychic powers only learnt later, such as Confusion.

One such power, Clairvoyance, allows Raz to see from someone else's perspective-literally. This includes how they view him, depicted through 2D doodles of Raz in a variety of outfits and situations. Most of these are unique to specific characters, and some of them change in different situations.

Examples of clairvoyance.

Characters that provide these views, left to right: Rainbow Squirts, Ford Cruller, Gloria's Theater birds, Linda the Lungfish, Milla's Dance Party dancers, and Lili Zanotto.

Details like that, and the way gameplay collectibles like Memory Vaults and Emotional Baggage contribute to the game's overall pacing and story, are yet another reason I dig this game. It feels very complete and lived-in, so-to-speak.

WRITING

Psychonauts was written by Tim Schafer (best known for his involvement in several classic LucasArts games, such as Day of the Tentacle and Grim Fandango) and Eric Wolpaw (best known for his work on the Portal series.)

Their writing is Psychonauts' biggest strength-and considering how many strengths this game has, that's saying something.

The game combines distinctly-dark humour with effectively serious explorations of mental illness and growing up, with a classic-cinema touch to it's plot-structure.

It's all really well-done, and these seemingly-disparate themes fit together into a peculiar coming-of-age story full of likable characters and genuine emotion.

And telekinetic bears. And goggles.

The comedy is perhaps the most well-known element of Psychonauts, and it's not very hard to see why.

This game is super funny. The funniest, actually.

Whether it's the simple absurdity of the camper's personalities (like absent-minded Dogen, who "blew someone's head up once... actually, it was four times", or Quentin, whose hip-hop-surfer-dude speaking mannerisms were supposedly based off those of the game's art director), or Raz's one-liners ("Well, here I am. At the top of an abandoned insane-asylum, wearing a straightjacket, talking to myself."), or the concepts of the mental worlds themselves-there's a lot to laugh at in Psychonauts.

A lot of it is rather dark in tone, and sometimes it seems to directly contradict the game's approach to mental illness as a serious topic (Clem and Crystal and Becky in Gloria's Theatre spring to mind), but I feel that works far better than if it were to take it either one-hundred-percent serious or one-hundred-percent flippantly. It balances itself out, somehow, so it's neither mean-spirited nor overly-cautious.

The serious aspects of Psychonauts' writing are excellent as well.

The whole construct of psychics and how they are treated (valued for their abilities, but often disregarded as people, seen as something that needs to be 'fixed', perhaps by way of lobotomy) and their other traits (Nearly all of the Psychonauts have strange, but interesting pet interests and specific speaking-patterns) can be read as a science-fiction variant of autism.

As someone with autism myself, I found the game's exploration of it to be particularly well-done.

It sounds sort-of insane to say a cartoon video-game like this is the first time I've seen a reflection of it that I've really connected to, but it's true.

More than issues with social interaction, more than peformance in school, more than anything, the thing I find I've struggled the most with is being 'different' in a way that's impossible to articulate. I have no frame of reference for the mind other than my own, no way to explain how it's different, no way for anyone else to explain what it's like for them. It's surreal, almost, to think about in that light.

So to see a game explore that element of it, which nobody really talks about, is stellar.

It's even more stellar for it to explore it between all the cartoonish humour and adventure-game puzzles, and whilst discussing mental-health in a similarly complex way.

Past all those themes, though, Psychonauts is ultimately a coming-of-age story. It's about growing up, and finding your place in the world, and coming to understand your parents and role-models better as people, and falling in love for the first time, and learning to empathize with people better. And it's about lighting small animals on fire with your mind.

These are not mutually exclusive.

One more thing I think worth mentioning about Psychonauts' writing is the way that the game utilizes interactivity and gameplay in environmental storytelling, and in it's pacing.

Perhaps the best example of what I mean here is in Milla's Dance Party, where a certain Memory Vault is built into the pacing of the level in a very specific fashion; if you don't collect it, you get the sense that something's missing or odd somewhere, thanks to the lack of a 'crux' to that mental world. If you do collect it while playing, though, it becomes a very notable point in the level's structure. It has a contrasting tone compared to the rest of Milla's mind, it prominently contributes to her character, and it provides a short break from the bouncy levitation-ball platforming.

It doesn't feel like an optional collectible at all, but at the same time it needs to be one for the experience of finding it-something you're not supposed to see-to work. It's a fine example of utilizing the interactivity of a video-game in a creative way.

ART

The visuals of Psychonauts have a unique, whimsically-dark style, with influence from Tim Burton, 1960s design and film, and contemporary cartoons. The super-spunky look and feel of even the most minor characters and elements is one of my favourite things about this game, and it's for-sure been a big influence on my own art.

I feel like you could pick out almost any object or person in this game-a tree, a random summer-camper, a machine used to travel inside one's own brain, a dead fish-and find something rad about how it looks.

Everything is so angular and cartoony and strange and I love it.

But don't believe me-see for yourself in these screenshots!

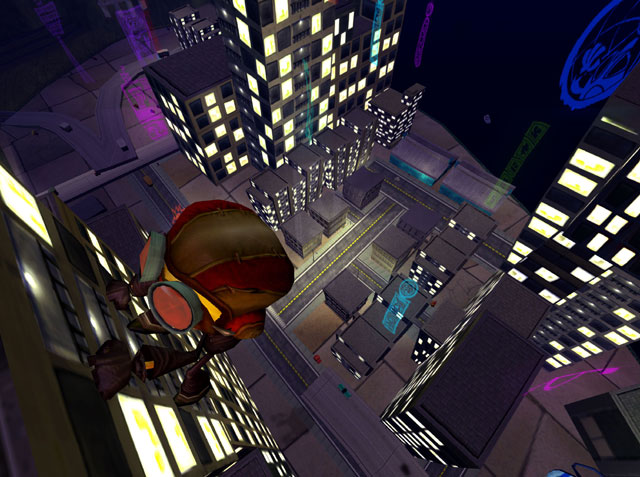

The twisting suburbs of the Milkman Conspiracy, and the Kaiju-movie city of Lungfishopolis.

How many games have you played where you get to stomp around a city of sentient lungfish as a giant monster?

Memory Vaults like these ones feature monochrome illustrations by art director Scott Campbell, put together in View-Master-like sequences.

(These two aren't in the same Vault, if you couldn't tell.)

The interior of Sasha Nein's secret laboratory.

Check out the midcentury furniture, and the sci-fi machinery.

It's not just the mental worlds-the 'real world' of Psychonauts has a fantastic cartoonish flair of it's own.